Ensuring financial security when retiring is a significant challenge that requires foresight. Statutory provisions determine the core framework around making retirement savings possible or impossible. Two drivers play a crucial role: solidarity and regulations. In this INSIGHT, I develop four possible framework scenarios around saving for the golden years. They can serve as the basis for governments, organisations, and individuals to plan how to best cope with retirement savings.

Retirement saving is paramount as it touches everyone’s financial security in their golden years. With an increase in longevity, an overall ageing population, advancement of technology, shifting economic trends, and a divisive political landscape, deciding how to best save for retirement is a wicked problem[1]. Foresight[2] about retirement savings aims to develop scenarios for dealing with the external environment, including societal preferences, understanding their implications, and deriving strategic options to best cope with them. It is about creating readiness for change.

Scope

Successful foresight requires, first and foremost, understanding the challenge at hand and defining the scope in which to envision plausible future scenarios.

Retirement savings is about planning for setting aside money to spend after retiring. It includes one or more goals, a method for when and how much money to put aside, and a financial strategy to manage the saved funds. The goals people want to achieve with their retirement savings approach can be subdivided into three complementary categories:

- Living costs. They ensure sufficient funds are available after retiring (and until death) to finance the current or aimed at living costs, like for buying groceries, paying the rent, covering health insurance, or going on vacation. Achieving the goals in this category is mandatory.

- Unforeseen expenses. Achieving these goals means being able to pay for unforeseen events, like fire or thunderstorm damages, unexpected elderly care after a stroke, or the death of a close person.

- One-off events. Goals in this category allow for coping with one-off expenses, like supporting the grandchildren’s college tuition, going on a world trip, or buying that small cottage near the lake. These expenses are typically optional and may be planned well off in advance.

To limit the scope of this INSIGHT, I only focus on the first category of retirement savings, that is, planning to finance living costs after retiring.

Exploring and discovering

Once the challenge has been well defined and the scope narrowed, foresight focuses on exploring the current environment for insights to generate knowledge about plausible futures. This means identifying trends and other possible drivers of change.

The insights from exploring current retirement savings frameworks can be classified into two categories:

- External environment. Environmental factors, like longevity, population growth, economic prosperity, or the consequences of climate change, are complex, if not impossible, to influence from an organisation, individual, or even governmental perspective. They serve as constraints to current and future retirement savings frameworks.

- Retirement savings systems. Governments, organisations, and individuals actively define the retirement savings systems. Key insights are individualisation, personal political preferences, and governmental interventions. Some of the most common retirement savings systems currently implemented by diverse countries are:

- Pay-as-you-go system. Active employees are paying the pensions of the retirees by contributing, for example, a percentage of their salary or a monthly fixed amount. This system exists in many Western countries, like Germany, France, Japan, Spain, and Sweden. No actual saving is taking place. Pensions are based on the promise that future generations with pay the retirees’ cost of living. Such a system is typically implemented as government-run social security or public pension programs.

- Defined benefit/contribution system. In defined benefit/contribution retirement systems, employees and employers regularly contribute to the system. At retirement, the retiree receives pre-defined payments to cover their living costs. The payments received are defined upfront and are typically related to the employee’s salary (in defined benefit systems) or are a function of the value of the actual contributions made up to the time of retirement (in defined contribution systems).

- Annuity plan. In an annuity plan, the employee makes regular contributions to the plan. In return, at retirement, the annuity plan provider pays stable cash flows after retiring until death.

- Employer-sponsored retirement accounts. Employees contribute a portion of their salary to their retirement accounts. Employers match a part or all of these contributions. The funds are either held in an interest-bearing account or invested in a portfolio of stocks and bonds. When retiring, the employee receives their total contribution typically as a lump sum.

- Individual retirement accounts. Individual accounts are similar to employer-sponsored accounts, except that employers do not contribute to the savings and individuals typically have greater freedom in how to invest the contributed funds.

A commonality of all retirement frameworks is that contributions by employers and employees positively impact their respective tax situation, e.g., by tax-deductible contributions.

Extensive foresight will consider both categories of insights when building and understanding plausible, probable, preferred, and wildcard scenarios about the future. To keep the length of this INSIGHT reasonable, I only focus on designing scenarios around possible retirement savings frameworks, assuming that the current external environment extrapolates into the future (which represents one possible scenario of the future external environment).

Building scenarios about the future

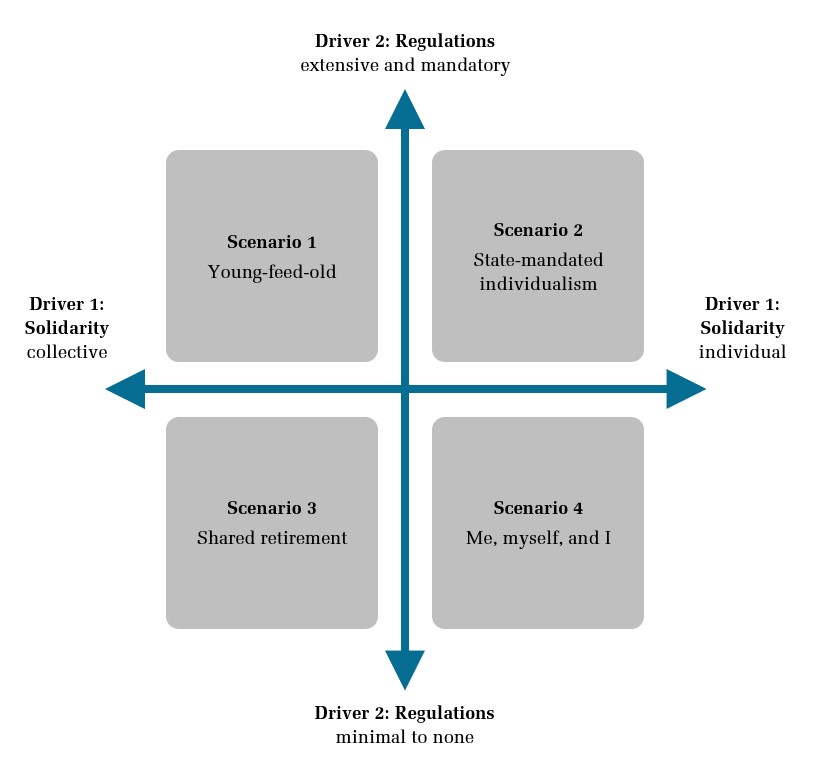

Analysing the insights gained during the explore and understand process step of the foresight activity leads to identifying two critical dimensions, that is,

- the degree of individualism versus societal solidarity on which the frameworks build, and

- how and to what extent governments regulate the contributions to and benefits from the framework?

For example, pay-as-you-go systems are based on a high degree of societal solidarity, whereas individual retirement accounts relate only to the respective employee.

Based on the two dimensions identified, I design four possible future scenarios, as shown in Figure 1.

- Young-feed-old. The first scenario builds on solid societal solidarity. Active employees contribute to paying for the costs of living of retirees. Retirement frameworks aligning with the young-feed-old scenario are easy to design and incur only limited risks, as they do not include a time dimension. They are without temporal uncertainty. The main challenge faced by this scenario is the willingness of the active employees to contribute “whatever it takes” to pay the retirees’ living costs. Depending on the personal perception of solidary, this scenario may or may not be a preferred scenario.

- State-mandated individualist. In the second scenario, the government mandates one or more retirement systems but leaves the implementation and the associated risks to individual or private organisations. This scenario strongly aligns with liberal beliefs.

- Shared retirement. In the third scenario, individuals, rather than government, decide which risks they want to share with other individuals and which they want to bear themselves. Solidarity is chosen by the individual rather than mandated by the government. The shared retirement scenario may lead to a multi-class society.

- Me, myself, and I. In the fourth scenario, the individual is free to save for their retirement as they wish. In return for this freedom, the individual bears all the risks, including the risk of not being able to finance their living costs after retiring. Private organisations may support them in their endeavour, but the choice remains with the individual. Personalised retirement plans may be driven by technology rather than human decision-making. The government only provides limited regulatory requirements and tax advantages, if any.

All four scenarios are plausible. Which scenario is preferable highly depends on the personal beliefs of the role of government in society and the preferred degree of burden-sharing by the individual.

Each of these four scenarios can be subdivided into one or more sub-scenarios considering specific shaping decisions, for example, how to define the contributions to be made (i.e., as a percentage of the salary, as a fixed amount, as a function of the expected annuity).

Figure 1. Two-dimensional foresight scenario matrix focusing on the dimensions of solidarity (1) and regulations (2)

Deciding

Once plausible scenarios of possible futures have been designed, governments, organisations, and individuals need to prepare for them. This means defining strategic plans to exploit the advantages and reduce each scenario’s risks separately. Rather than offer detailed strategic plans for each scenario, this INSIGHT gives reign to the reader’s imagination, presenting only some initial ideas.

Planning for scenario 2 – state-mandated individualism could lead to developing investment advisory services that ensure regulatory compliance and maximise personal freedom in structuring and managing saving for retirement and wealth consumption thereafter.

Under scenario 3 – shared retirement, asset management firms could, for example, identify target customer segments that share retirement goals and offer bespoke solutions. Investment risks could be shared within each customer segment without affecting other customers.

Conclusion

In this INSIGHT, I have described how to derive future scenarios concerning retirement savings. Foresight is about plausibly judging what may happen in the future and planning how to exploit change and reduce risks. Foresight is about big pictures of the future rather than nitty-gritty details. Foresight is about creative readiness for change.

[1] A wicked problem is a problem with many interdependent factors. It is often incomplete formulated and therefore hard to grasp.

[2] Foresight (also called futures studies) the ability to judge correctly what plausibly may happen in the future and plan possible scenarios based on this knowledge.